Reminiscences

If you wish to contribute a reminiscence or comment, please send it to rememberingraz@gmail.com

Reminiscences

Joseph supervised my DPhil between 1997 and 2000, andinvited me to visit Columbia with him in the fall of 1998. Those opportunities have framed much of my life since. Joseph’s generosity of mind and disposition is likely well known to anyone reading this page. As distinctive, was his particular way of seeing the world, be it through the prism of philosophy, photography or more quotidian observation.

In December 2013, Joseph and Penny stayed at my home in North Bondi, Sydney, while visiting Noam. The house was at the edge of the Ben Buckler headland with an undisturbed view of the ocean. Showing them around, I took them first to the balcony and Joseph smiled widely. We later went up to the rooftop garden. Joseph smiled again and said: ‘I noticed this as soon as I arrived.’ He wasn’t, of course, looking at the horizon, but down to the foot of the cliff where the water met the rock. ‘This is a truly wonderful rock.’ The rock that had captured him was an oblong smoothed by the ocean, with a circular dimple in its middle, not unlike the eye of a whale, streaked green with moss and lichen. Joseph smiled again and said: ‘I will spend a lot of time looking at this rock.’ He had, among all the obvious beauty, fastened upon the quietly sublime.

Professor Andrei Marmor, Cornell University

The little story I want to tell is about the best advice I ever got in my professional career. It must have been around 1985 when I was an M.A. student in philosophy at Tel Aviv University. Somewhere in the corridors of the humanities building I see a tall, handsome, and very American looking fellow, clearly lost in the maze of the corridors, so I offered my help. My name is Robert Nozick, he said, and I'm looking for the philosophy office. I lead him there and on the way we chatted for a while. I told him that I'm interested in philosophy of law, and just beginning to figure out where to apply for my doctorate studies. Well, he said, that's an easy one; if you want to work on philosophy of law, there is only one place you should apply to, go to Oxford to work with Joseph Raz. And that, of course, is exactly what I did. I never saw Nozick again, and never had a chance to thank him for what turned out to be the best practical advice I have ever received in my academic life.

Professor Julie Dickson, University of Oxford

The main thing I want to say is to send my sympathy and my love to Penny and Noam and to say how very sorry I am for their loss. But just a couple of reminiscences about Joseph come to mind as well. One is about his enormous intellectual modesty. When I was a graduate student of Joseph's, if during our supervision meetings he thought that my work could benefit from reading certain things, then so long as he did not write those things, he would explain to me clearly (though never in a patronising way) what he thought I should read. But if it happened to be something that he himself had written, he would instead go all ‘sotto-voce-intense-mumbling’ on me. ‘Yes, and well, I suppose you could also look at something I have written on this, it is mmmmrgtsggk brlltwsssmn in the journal of glllbbbmmmrsng.’ ‘Sorry, what was that?’ I was at least prepared to ask. ‘Oh just a short something I did in mmmthrrrwwwsss bllllrgghh.’ Joseph would not explain further, and I, in my stubborn Scottish pride, would not ask further. So supervisions at that point would reach a benign but somewhat weird stalemate of me frowning and pretending to write something down that I had not heard at all and Joseph looking out of a window or some such. I would then spend the next 6 weeks attempting to hunt down mmmmrgtsggk brlltwsssmn in the journal of glllbbbmmmrsng in a variety of libraries around Oxford. That was good though: it made me feel always that I was going on a ‘quest’ to hunt references down, and indeed that is just one of the many ways in which Joseph gave me a strong sense that doing intellectual work was like a quest, an adventure, and that it was the work itself that drives that quest, not us: that we serve the work, as it were. There was also an occasion when, during a supervision, Joseph opened a small cupboard in his Balliol office to reveal a veritable shedload of off-prints of an article he had written sent to him by the publisher. ‘Look! It is ridiculous! What am I supposed to do with these?’ he asked. A couple of days later I discovered that a kind of answer had come to him when I went to my pigeon hole in Holywell Manor, Balliol's graduate annex where I lived, to find that I had received from Joseph one of the off-prints in question (I think he sent them to all his students). It came with a classic note that I will never forget, and it resonates the better with me still in our current times of sometimes relentless self-promotion: ‘I have too many of these. Give it to anyone, or just throw it away. Joseph.’

The second reminiscence is just of Joseph's immense commitment to, and kindness to, his graduate students.

My intellectual debt to him is profound, although, as with all his students, he never encouraged me to follow his own thinking, and wanted always his students to have intellectual independence and to do their own thing. But it’s his sensitivity and kindness, especially (but not only) in the early years of my career, when I struggled to find the right place for me to work, and was, for a variety of reasons, not very happy in my professional life, that I carry with me always.

Amongst other things, to try to help me, and in a wonderful sort of ‘moving in mysterious ways in the background’ manner of facilitating things, Joseph took me to the pub for drinks, met me for pizza lunch, suggested we met up to go to films at the cinema, wrote to others in the profession working at institutions where I was moving to, suggesting lightly that they meet me for lunch or coffee to help me settle in, responded so supportively to all manner of emails I sent him, listened many times over to my troubles. And much more. But I hope this conveys the sense of it. I try in my own ways to pass on what I can of some of this with my own students, both undergraduates and graduates. I am so happy that he was a (big) part of my life, with all this, and also with his eye-rolling at pretentiousness (and at many other things!), mischievousness, and giggling.

With love, Julie Dickson

Les Green, Emeritus Professor, University of Oxford

Tutorials with Joseph could be, as John Gardner used to put it, an ‘eye-opening and eye-watering experience’. Yet many of us became Raz-recidivists. After finishing our courses, we applied to the D.Phil., pleading in our applications to be assigned Raz as supervisor. Yet we knew what we were in for: it would be demanding but intellectually transformative. We just could not predict how.

My later friendship with Joseph and Penny was also transformative in other unpredicted, but welcome, ways. Over the years I was a tenant, a houseguest (i.e., freeloader), and an occasional travel companion. I first welcomed myself to the house on Lincoln Road by breaking a dining chair and then losing Joseph’s cat, Fluffy, for several terrifying days. That turned me into a cat person. I eventually got my own cat and learned to relax whenever she decided it was time for a weekend break.

And Lincoln Road had a garden! Penny’s doing, it was an urban oasis where we gradually learned to know and love plants. And then garden tours. And Gardeners’ World. Much later, when Penny and I were colleagues at Balliol, I bought an old house with a ramshackle garden. Penny was first on site, to explain what I trouble I had let myself in for. Optimistically, she gave me several garden chairs. It was a few years before the garden would merit sitting in, but I rarely had clean fingernails after that. I was immensely proud when Joseph and Penny came up and admired it.

Then there was art. In Oxford, Joseph introduced me to Hayter prints and to Rie ceramics; in his flats in London and New York, to photographs, including many by Joseph. At Balliol, Penny nudged me onto the Portraits Committee: one of the most dangerous jobs in an Oxford college. Along the way I learned how to look at pictures. One day, Joseph was scrutinising some paintings I had just hung at the house. He said nothing at all. To fill an anxious silence I said, ‘This one is my favourite, but if you are wondering which is the best, it is that one over there.’ Joseph looked baffled. ‘If that one is the best, then why isn’t it your favourite?’ Once again, I felt the shiver of post-traumatic stress that every Raz-recidivist knows so well.

Cats, gardens, art, and jurisprudence: Joseph transformed my life, as he did the lives of so many others. May his memory be a blessing.

Professor Wil Waluchow, McMaster University

My most cherished memory of Joseph was the time, shortly after I got my DPhil, when he commented on a paper I had written for a seminar he organized. In the paper I set out to critique his exclusive positivism. He began by saying this, words I will forever remember: ‘Philosophy is a funny discipline. One can greatly admire and respect someone’s work while at the same time disagreeing with virtually everything he has to say.’ He then went on to demolish my arguments — in that kind, yet utterly devastating manner he often exhibited. A wonderful man who will be missed.

Professor Jonathan Dancy, University of Texas at Austin

I became acquainted with Joseph quite early on in my career, but our friendship blossomed during the year that I had a Visiting Fellowship at All Souls in the early 90s. Joseph invited me regularly to lunch in Balliol and we talked about all sorts of things. One of the proudest moments of my life was when he said that he and I thought in the same sort of way. I suppose this meant that behind the visible disagreements there was a commonality of approach. It did not mean that he gave me an easy, or even an easier, ride Rather the opposite, if anything.

Professor Anton Fagan, University of Capetown Faculty of Law

Raz supervised or taught several people who have gone (or went) on to become accomplished legal philosophers in their own right, such as John Gardner, Leslie Green, Andrei Marmor, Timothy Endicott, Scott Shapiro, Julie Dickson, Timothy Macklem, and Grant Lamond. He also supervised me, who has not. I suppose it just goes to show that, once in a while, everyone gets to back the wrong horse.

Nonetheless, Raz’s supervision was inspiring: though not necessarily in the ways you would expect. I remember my first supervision meeting with him, at which I arrived with some trepidation. A few days earlier, I had been told that another DPhil student, after his first meeting with Raz, had spent his entire train journey back to London in tears. The draft chapter which I had submitted to Raz had taken me months to write. And, by this time, with three degrees under my belt, the last of which had required me to write more than fifty philosophy essays, I thought myself a competent writer. However, Raz started the meeting by informing me, very politely, that I needed ‘to practise some verbal hygiene’, and then went on to explain that I had used a key concept (I forget what it was) in six different ways. The distinctions were subtle, and I am not sure I grasped all of them. But I got the main point, which was that legal philosophy is an exacting discipline, and I was going to have to up my game.

Raz did not condescend. He engaged with the work I submitted to him in the way he would have engaged with a conference paper or article written by one of his peers. So, if he thought an argument which I had made was weak or wrong-headed, he told me so and expected me either to defend or to abandon it. On one occasion, having had every one of my arguments in defence of a position I had taken pretty much demolished by Raz, I in desperation appealed to the fact that his equally eminent Oxford colleague, Ronald Dworkin, had expressed the same view in several of his writings. Raz wryly responded: ‘Well, Anton, the fact that Dworkin has made a mistake is no reason for you to repeat it.’ Again, the lesson was learned. Jurisprudential disagreements cannot be settled by invoking the authority of others. They are won or lost only on the strength of the reasons and arguments advanced for each of the competing views.

Raz was not unkind. But he could be impatient with academic pretension. In a postgraduate jurisprudence seminar which he was giving on the notion of coherence in the law, an American student asked one of those questions which is really a statement, dressed up as a question, aimed in part at exhibiting the speaker’s intellectual prowess. The question went on and on, in ever more convoluted circles, and throughout it Raz kept his gaze fixed on his notes. When the question finally came to an end, Raz looked up momentarily, said ‘No’, and continued the seminar as if it had never been interrupted. Though I am not certain of this, because it was almost thirty years ago, I think that the student in question was Neil Gorsuch, who was then doing his DPhil under John Finnis, but is now a judge of the US Supreme Court, having been nominated for the position by Donald Trump.

Professor Ian Rumfitt, All Souls College Oxford

Although I am no expert, it seemed to me that Joseph had long occupied, in moral and political philosophy, the position which my own esteemed supervisor, Michael Dummett, held in logic and metaphysics — namely the figure who, in Oxford at least, was the setter and upholder of standards, partly through his teaching, but chiefly because of the extraordinarily high quality of his work.

It was, though, Joseph's rich cultural interests, rather than philosophy, which had originally brought us together. When I was a JRF at Balliol, we discovered that each of us would have done something interesting at the weekend and we took to comparing notes on Monday mornings. I would have been to a concert or opera, Joseph to an exhibition or a play at some theatre I had never even heard of in the depths of Islington. I fear we rather looked down on those colleagues who had spent their Saturday evenings slumped in front of ‘Match of the Day’. That was a bit unfair: when I became a tutorial fellow, a few years later, I too was zombified by the weekend. I am, though, grateful to that sense of fellow feeling for having started a friendship which greatly enriched my life. I have known many cultured people, but no one else who matches Joseph's refined appreciation of such a wide range of the arts: theatre, music, painting, sculpture, architecture, and of course photography.

Professor Annalise Acorn, University of Alberta

I was tremendously lucky to have attended seminars given by Joseph in the mid 1980's during my BCL. Of course, one knew that one was in the presence of greatness. But so much of what he said was so intricate and so minutely reasoned that it was pretty much impossible for me, most of the time, to feel like I was getting it. But trying to stay with him and trying to get it was still so rewarding because from time to time he would just deliver some dazzling jewel - an amazingly clear, simple and enlightening statement that nobody else could have formulated with such delicacy and forthrightness.

One such jewel that I will always be grateful for was an explanation he gave of the task of the legal philosopher. He said something like this: ‘As legal philosophers our task is to perceive things with as much sensitivity and acuteness as we can and then to construct conceptual frameworks to illuminate those perceptions.’ I've tried over the years to come back to that statement in everything I write - both as a ‘how to’ method of writing and as a way to evaluate what I've written.

On the day of my first BCL exam I came into the Examination Schools, all dressed up in subfusc and incredibly nervous. Joseph Raz as Chair of Examiners that year was standing at the front of the room. I sat down in an empty seat and started to write. A few minutes in, I noticed that Professor Raz was coming to speak to me. What can this possibly mean? But then he said, ‘Are you in the right seat?’ ‘Probably not,’ I answered. He laughed! And then he explained that there was a seating plan and that I was supposed to be across the room. I thought well, even if I fail the exam, at least I made Joseph Raz laugh. But what sticks with me today is how careful and gentle he was in correcting me about where to sit without making me feel flustered or reprimanded.

Professor Nicos Stavropoulos, University of Oxford

When I first arrived at Brasenose to start the DPhil more than 30 years ago, a note from Joseph was waiting in my pigeonhole. I vaguely knew who he was but had never met him. A few days later we met in his room at Balliol (Staircase XIII on the first floor I believe). He was nothing like the other dons I had seen around the college quads. He said he was not my supervisor — Ronald Dworkin was — but was standing in that term because Ronnie was in New York. He asked me to write something and come back to discuss it. We agreed that I’d write about something I had recently read. I took the entire term to produce a paper on a then novel position about legal interpretation that drew on Kripke’s and Putnam’s work on meaning and necessity. We then met to discuss my piece and I had the experience I later learned was typical of graduate students working with Joseph. Forceful is an understatement of his style of critical feedback. He announced to me that the position I was commenting on had nothing to do with what I had declared it to be all about. I was not amused and pushed back hard. I found the heat of the exchange disturbing, but he seemed to be in his element.

Following that meeting, Ronnie Dworkin was back from New York and I had no further one on one meetings with Joseph for the rest of my time as a graduate student. My philosophical attention was elsewhere, but I followed his seminars on authority, held in Room XXIII under the Balliol SCR, and I started working my way through his work. He was friendly throughout, and by the time I finished the DPhil I realized that I was quite fond of that deeply unusual, brilliant man.

He was extremely supportive once I returned to Oxford to start teaching — he was a legendary mentor and supporter of former students and other junior colleagues. At seminars and workshops he was his usual self, direct, forceful, unsparing, but I had learned how to handle that and shared in his delight at being part of the fray. He was a different man outside the seminar room, courteous, gentle, funny. Our friendship grew over the years. I will sorely miss our dinners in London, when he would march me down the streets of Marylebone at high speed to one of his local favourites. I will miss his love of industry gossip, his pithy put downs, his fine nose, and disdain, for the pompous and the phony, his delight at hearing news, personal and professional, of others in the business. I will miss the excitement of finding that he had just posted a new draft and dropping whatever I was doing to start reading it. I will even miss his full force frontal take no prisoners attacks on whatever claim I might be minded to defend at one time or other. He made us all think more carefully about everything.

Ruth Chang, University of Oxford

Remembrance of Joseph Raz

I first got to know Joseph when I was a Junior Research Fellow at Balliol where we became friends. Perhaps somewhat surprisingly, we ended up not talking philosophy much, in large part due to my crude midwestern American ear and his soft-spokenness, which made it difficult for me to catch his insights, which came thick and fast. But we talked about many other things. Photography. Architecture. Gossip about the College and other philosophers. His son, Noam, of whom he was very proud. Joseph was irreverent, perceptive, and a connoisseur of human fineness and foible.

He was also the consummate ‘kitchen’ philosopher; someone whose eagle eye was always trained on human life as we live it, with all its complexity, ambiguity, and indeterminacy. One thing that made his way of doing philosophy so, well Razian, was his use of nuanced, often quite abstract distinctions and arguments to illuminate large, messy, human phenomena such as well-being, normativity, social practices, value, the law, autonomy, authority, and so much more. He was an architect of ideas -- there were always precise drawings but they were always in the service of a beautiful edifice of understanding.

Over the years, Joseph and I lost touch, though I would occasionally email him for advice about this or that, and he was always generous and wise. I remember putting on a retirement party for him in New York and many of the Great and the Good came along. I think he was pleased but also felt awkward about being celebrated in this way. I remember being struck by the way he occupied space in contrast to others; the party had a lot of Big Personalities who expanded their space with clusters of the adoring around them. Joseph was instead like a concrete block -- very firm in the space that he himself occupied but thoroughly uninterested in expanding it. If the adoring wanted to cluster around him, that was up to them. (They did).

He and Penny were a beautiful, deeply connected pair. They seemed to have had their own private language, whispering mysteries that sounded like English but that only they could understand. She was fiercely protective of Joseph and seemed to me -- and still does -- like an Amazonian warrior.

My greatest compliment has been the assumption on the part of many that I was Joseph’s student. I was never his student, although anyone who has the privilege of getting to know him can be nothing other. Joseph was ferocious but gentle, exacting but expansive in his thinking, and compassionate but didn’t suffer fools gladly. I will miss him.

Professor Christine Sypnowich, Head of the Department of Philosophy, Queen’s University, Kingston, Canada

I was fortunate enough to have Joseph Raz take on the supervision of my dissertation at two different points in my DPhil at Balliol College in the mid-1980s.

I recall being rather shell-shocked by Joe’s fierce scrutiny. But I was also grateful for his generosity – he gave what were often hours per session to go over my work with such care and attention. I remember after a couple of hours of grueling criticism, I asked plaintively if there was anything at all of value in what I had written, at which point he reassured me that I should understand that he had his own perspective which I need not share. Somehow, I found that a comfort! I benefitted enormously from Joe’s guidance which set such a high standard of analytical acumen and rigour.

Joseph Raz was an outstanding scholar of significant achievements across a range of subjects in law and philosophy, and though he lived a long and full life, it is a sad loss. My thoughts are with Penny, Joe’s family, and his many friends and colleagues all over the world.

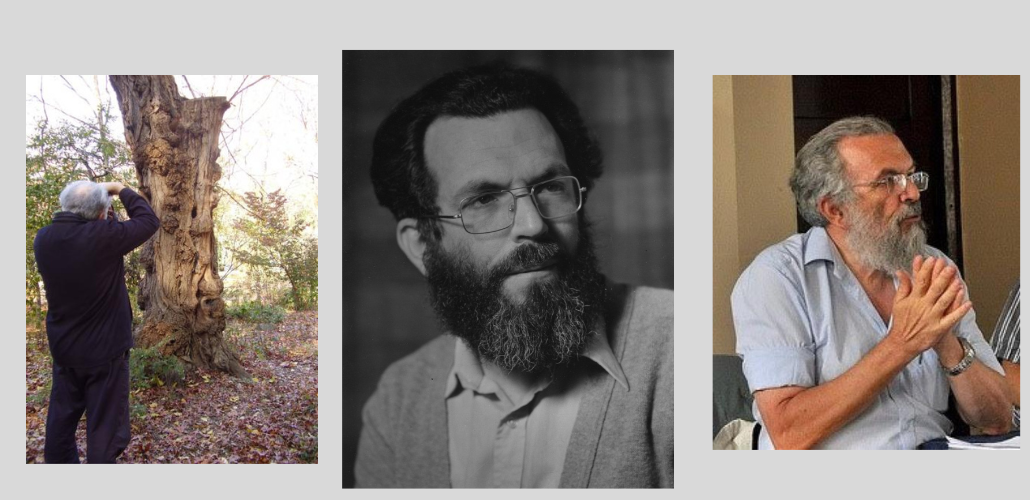

Penelope Bulloch and Joseph Raz, New York. Photo by Alex Ward

Dr Penelope Bulloch, Emeritus Fellow, Balliol College

To all those who have written to me and to Noam with sympathy and support: we are so grateful.

Joseph did not want a funeral. He left his body to the London Anatomy Office, for education or research, and it has been accepted. They know he was a Professor, and told me ‘now he can go on teaching’.

Plato makes Socrates, on trial for his life, tell the jury why he will not stop talking about philosophy: ‘it is the greatest good for a man to discuss virtue every day and those other things about which you hear me conversing and testing myself and others, for the unexamined life is not worth living’ (Apology 37e-38a).

Talking philosophy with students and colleagues was at the centre of Joseph’s life and he continued his seminars at Columbia Law School until the end of 2018, after which he no longer had the strength to continue. From 2020 the seminar series he gave with Ulrike Heuer at University College London enabled him to carry on the discussions, initially following the format he had developed at Columbia and later on Zoom because of the pandemic and as he grew weaker. The seminars covered questions on Practical Reasons and Normativity: ‘Reasons and Rationality’ (2020), ‘The Role of History for Understanding Normativity’ (2021), and ‘Normative Powers’ (2022). Like all Joseph’s work, they dealt with major problems: Can morality change? Does the existence of a normative power (e.g. to make a promise or enact a law) depend on the desirability of someone having that power?

Medical students face other problems, and the questions his body will make them confront are different. But that’s what he wanted to be involved with: posing questions.

Professor Pablo Navarro, Universidad Nacional del Sur and Universidad Blas Pascal

The death of Joseph Raz surprised me and has left me with a deep melancholy. I remembered my stay in Oxford, and a multitude of memories of those days in 1995 have surfaced.

In particular, I evoke his kindness and patience when I arrived in England, with my very poor English and many fears in the face of that academic adventure.

For example, the first time I met him at Balliol College, I had just arrived in Oxford and asked Joseph to tell me where the Bodleian Library was on a huge map I had bought from a Carfax store. My naivety made him laugh and he told me that it was easier for him to accompany me to the Bodleian than to find it on my map.

On a handful of occasions, we discussed some of my work on the effectiveness of law, the open nature of legal systems, and the reception of norms. After meeting with him, I almost always thought that my ideas never lived up to his demands. However, those conversations were still hanging around in my mind and little by little, once I overcame the bitterness of abandoning many of my original theses, their criticisms had a brighter light. In general, his ideas had flowed spontaneously and somewhat run over in the conversation. It was not easy for me to understand his arguments, but finally, when I managed to fleetingly capture the ideas that Raz had anticipated, I was deeply moved by their depth and originality.

Photographers: Gillman & Soame, www.gillmanandsoame.co.uk

Professor Matthew Harding, Melbourne Law School

I personally feel I owe Raz a huge intellectual debt, and I am grateful that he has left us all with so much to think about and discuss.

Professor William Edmundson, Georgia State University In 1989 I had just started my teaching career and was anxious to get something published. I had read that doing book reviews was a good way to break in, so I offered my services to the journal Law and Philosophy. Joan MacGregor wrote back, suggesting I review the new, second edition of something called Practical Reason and Norms that Princeton U.P had brought out in the U.S. I said yes, despite having never heard of the author, Joseph Raz.

As soon as I got hold of my (free!) review copy I read it straight through with a mounting sense of excitement, almost of awe. I was familiar with Hart and Dworkin, but Raz’s analysis bowled me over with its greater depth, generality and precision. Above all, there was something visually suggestive about it. The picture of second-order reasons protecting first-order reasons by keeping other reasons at bay reminded me somehow of the stable configurations that can settle out of the flux of pixels in John Conway’s game of Life, one of the early computer games.

Writing up the review made me anxious. Joseph’s second edition was intended to answer criticisms of the first, many of them raised in symposium papers collected in a thick, dedicated volume of the Southern California Law Review. I wasn’t sure some of Joseph’s responses were sufficient —if I’d understood them correctly. Finally, I decided to send Joseph my draft review and ask whether I had correctly represented him. He wrote back, saying, essentially, that I was on my own. It was his policy, he said, not to tell others how to interpret his written work. The lesson I took from him was: the words one writes must speak for themselves. The author’s job is to take care that they do.

I met Joseph later at meetings of the Analytical Legal Philosophy Conference, and later still in Oxford and London. It gradually dawned on me that our respective philosophical orientations were not as well aligned as I had hoped. Even so, it was delightful to be his guest at a meal in Marylebone (more a delight than at Balliol, whose food he apologized for), and to be able nearly to match him, almost stride for stride, in a postprandial footrace (so it seemed) to a concert hall across town. A man who will always be worth trying to keep up with!

Professor Dale Smith, Melbourne Law School

I was so very sorry to hear about Joseph’s passing. I was fortunate enough to have been supervised by him for a couple of terms as a DPhil student many years ago, and he was unfailingly kind, even when he may have had reason not to be. Like everyone who is exposed to Joseph’s ideas, I have been profoundly influenced by them. Few philosophers, I think, have developed frameworks for thinking about so many different aspects of our lives. And the work of few philosophers has been so relevant, not just to academic debates, but to a well-lived life and the practical problems that arise in the course of that life. This was brought home to me recently, when I found myself drawing on Joseph’s work on practical reason when trying to explain to my 13-year-old son a decision I had made with which he profoundly disagreed. He still wasn’t persuaded, but he at least had to acknowledge that he could now see my point of view! Joseph will be deeply missed, not just for his towering intellect but also for his practical wisdom. He was truly a giant of the field.

Professor Katy Barnett, Melbourne Law School

I never met Joseph Raz but I was hugely influenced by his work, and I count myself as a ‘Razian positivist’. I was very sad to hear of his death. I had just bought his latest book, The Roots of Normativity (published in 2020).

Professor John Tasioulas, University of Oxford

Much has been made of Joseph's 'fierceness' as a teacher and colleague, not least in the recent Times obituary, and there is no doubt more than one grain of truth to this assessment. But I think it's important to contextualise it in at least two ways. Like any great thinker, Joseph faced the special problem of finding a modus vivendi with lesser intellectual vessels. Some may respond to this challenge by shrinking from serious engagement. We can be thankful that this is not the path Joseph chose - as shown, most obviously, by his Herculean commitment to graduate supervision. Added to this, of course, is that Joseph was a great philosopher whose professional circumstances meant that he was often thrust among lawyers, many with philosophical aspirations. Lawyers, as a group, are not known for having a strong philosophical background but, equally, they are not generally the kind of people who would allow such a fact to diminish their robust sense of intellectual self-confidence. In the circumstances, I was often led to reflect that, despite all his supposed fierceness, Joseph was also capable of achieving stunning levels of patience and forbearance.

He could be surprisingly uncompromising when it came to practical arrangements, such as the precise format of a seminar discussion. This was usually innocuous, although it was an attitude that did rather belie his theoretical commitment to the incommensurability of values. As in the case of Wittgenstein, however, I think this was a quality of his that some acolytes found all too easy to emulate. Lacking Joseph's intellectual gifts, this attitude did not exert the charm or fascination that it could in his case. It is, of course, always risky to turn one's intellectual heroes into moral heroes. And I think Joseph did more than many prominent philosophers to discourage such idolisation. One thing, however, I can say with absolute certainty. I never detected in him even one ounce of professional jealously or careerist grievance. And that is surely quite something given the desperately competitive nature of academic life.

One final observation. Joseph was a personally impressive figure, something evident even to those who had no idea, or no very clear idea, of his staggering academic achievements. Of course, the imposing prophet's beard couldn't have hurt in encouraging this impression, but it was only part of the story. I remember on one occasion dining with him at his local Moroccan restaurant. The waitress leaned over to me and whispered 'He is a great teacher, isn't he?'. On another occasion, when he had dinner at my family home, my elder son who was not yet a teenager, said after Joseph had left: 'One day people will ask if I ever met the great Raz, and I will say yes, I gave him directions to the loo'.

He was a great thinker and a special human being. We are all diminished by his passing.

Photographers: Gillman & Soame, www.gillmanandsoame.co.uk

Professor Kristen Rundle, Melbourne Law School

Joseph Raz was immensely kind to me personally, expressing real interest in and encouragement for my less orthodox ways into questions of legal philosophy. In the last one-on-one conversation I had with him, at a conference in Sydney, we talked about how the idea of the rule of law had been so appropriated by neoliberalism that there seemed little point in saying much more about it. And yet, around a year after that conversation, he chose to revisit his seminal essay on the topic - his 1979 'The Rule of Law and its Virtue' - to update its analysis. That essay, published in the OJLS, now stands alongside 'Virtue' as a leading work of legal philosophy on the rule of law. But to me, it was the fact of the revisitation itself that said something more important than the analysis contained within it. It showed his commitment, as a scholar, to not giving up on an idea that, appropriated for particular ideological causes or otherwise, remains central to the inheritances of legal and political thought with which we live and work. He had responsibilities towards that idea, and he continued to discharge them. I admired that profoundly.

Joseph Raz gave me a lot to figure out, at times striking terror in my heart and mind in my efforts to do so. But perhaps more than any other, his work provoked me to learn what I needed to understand to say what I wanted to say, while the man himself encouraged me to do it my way, and reminded me - indeed, all of us - of the responsibilities of the scholar towards the ideas with which they engage. His passing is a giant loss to us all.

Professor David Heyd, The Hebrew University of Jerusalem

I guess that some of you (or maybe even most of you) share my experience of never having received a direct verbal compliment from Joseph, such as ‘this is a terrific article’, or ‘what a splendid argument’. But he had his own indirect, usually non-verbal way of conveying to you some measure of appreciation. Yet we had to learn to interpret these non-verbal ways and by that avoid being offended.

In the competition who knew Joseph first, I am in a good position (although Peter Hacker and Avishai Margalit and maybe a few others can boast to have preceded me). I was his first teaching assistant in the department of philosophy at the Hebrew University when in 1968 he returned from Oxford with his fresh DPhil.

When I brought him the first batch of over 100 essays of his students in the Introduction to Ethics, after days and nights of work of filling the pages with comments in red ink, he browsed through them, invited me to coffee and cake, but said nothing about his impression of my TA work. I was a bit disappointed and went home feeling that I did not live up to his expectations.

But a few days later I got a message from the chair of the department telling me that Joseph approached him with a demand to raise my salary by 50% due to my diligent work.

Throughout the remaining 54 years of our relationship I had to rely on my power of interpretation of such indirect signs. And as many of you have probably experienced, there was no way to ask Joseph directly whether our interpretation of these signs was correct, as we thought. Rather than give us a yes-or-no answer Joseph would probably produce all the reasons for doubting our epistemic confidence. But in devoting much of his precious time to teach us skepticism he would demonstrate that after all we were correct!

Professor Timothy Endicott, University of Oxford

When Joseph and I met to discuss my first paper when I started the DPhil in Oxford, he said, ‘I like this, but you won’t believe me once we’re through.’ And then he dismantled it. That session set the pattern for my work. I would spend three weeks or a month writing a paper, Joseph would meet me the day after I sent it to him, and after our discussion I would leave his room with nothing left.

What a great thing. He had focused so intently on what I had written. The experience opened the horizon of my expectations. It was clear that demolition was not his purpose; that happened to be the result, given what I had written, when he thought hard about the problem itself, and said what he thought. He made it seem to me that it wasn’t impossible to do something worthwhile – just more difficult than I had realised. At first I thought that Joseph found it easy, but when I got to know him better I learned that he did such prodigious things with the philosophy of practical reason through hard, sustained work. He set an example of fearlessness and care and imagination.

Jonny McIntosh, Balliol College

I have fond memories of talking with him, both in the seminar and at lunch afterwards. He was strikingly generous with his time and his feedback on my ideas, even though they were invariably not very good, and I count myself luck to have talked with him --knowledge enough to make me aware of what those who knew him well have lost.

Professor Irit Samet, King’s College London

The older I grow the more I realise the extent to which Joseph was a supervisor like no other. I was not a typical student of Joseph’s, having chosen to write about metaphysics, medieval philosophy and moral psychology. I now know that I had the rare freedom to go wherever my intellectual curiosity led me only because I had Joseph’s backing. I knew that as long as I engage seriously with the material he will be there for me: probing, suggesting alternative ways of thinking, referring me to books and scholars that were not on the menu of mainstream DPhil students in the law school. And while he was in one sense a very much hands on supervisor on both intellectual and pastoral levels (which in my naivete I took for granted) he never ever imposed his own view of the issues I chose to discuss. In fact, unless I could find it in his writing, I often couldn’t really tell what was his view on the issues that engaged me. As he repeatedly said, it’s how you get to your conclusion that is of real interest to me, the conclusion itself much less so. And so, like all his students, I always have a little Joseph voice sitting behind the writing hand, urging me to think and rethink my argument, never pose a strawman as a foil and be totally clear about my assumptions. This voice made my work infinitely better than it would otherwise have been. I can hear it speaking when I read the work of other students of his, my brothers and sisters in the Raz family. I still smile when remembering the joy I felt when I set with him on the last chapter of my DPhil, two weeks before I gave birth to my first child, and he said to me (for the first time, of course) ‘that was a good chapter’. And the memory of him gently holding her as a new-born now brings a tear. He will leave forever in our heart.

Professor George Letsas, University College London

My first encounter with Joseph was in 2000 when, as a master's student at UCL, I asked a question at a jurisprudence seminar on the topic of freedom. The speaker, an established figure in the field, quickly dismissed my question as misconceived. Joseph was in the audience and next to ask a question. He began by saying: "I do not think you answered the previous question at all". Afterwards, he very kindly approached me to explain further why he thought the speaker's argument was flawed. I was deeply honoured but I was hardly able to follow his explanation. It wasn't just his unique combination of depth and economy of expression. Joseph's intellectual brilliance was reflected in the way he talked to you: slow paced, going back and forth between eye contact and an unfocused look towards the background, accompanied by an upward tilt of his head. It was as if every word he uttered was meticulously being distilled, there and then, from a complex and powerful philosophical machine. You couldn't help getting distracted, and amazed, by the whole process.

After occasional encounters at conferences, we ran into each other again in New York in 2010. He came up to me at the NYU colloquium and said, "We should have lunch". To my surprise, he proposed Sunday and recommended a restaurant uptown. I had no idea what to expect. We talked for more than two hours about everything except philosophy: politics, art, current affairs. He then asked if I was doing anything else that day and offered to show me around the Columbia University campus. The tour included his favourite bookshop, the NYC cafe that features in the sitcom Seinfeld, and the Columbia Law School building. Late in the afternoon, we ended up having coffee at his apartment which overlooked the Hudson River, and whose minimalist interior looked straight out of a design magazine. Joseph's known generosity, warmth and kindness were in full display.

In the next ten years we would see each other regularly in London, usually in seminars, sometimes for lunch or dinner. In seminars and written feedback, he was always charitable and constructive to my half-baked ideas. One time he picked up something obscure I had said as a respondent to a paper and turned it into a clear and sharp point, before adding: "but of course George has provided no argument for this". He was right. In personal conversation, he was always relaxed, friendly and warm - just like that day in New York. I feel that our interaction benefited from the absence of any roles: I was not his student, his disciple, or his colleague. I understood early on that, as all great thinkers, Joseph had a complete philosophical system worked out. The point was not to critique, but to understand and admire. Both the work and the person.

Joseph Raz with George Letsas

Professor James Penner, National University of Singapore

Professor David Enoch, the Hebrew University of Jerusalem

I was not a Raz student – a well-known concept to anyone in the field. But while doing my PhD at NYU I took the subway uptown to attend the seminars by the person whose name I had heard from my very first year studying law, up at Columbia. He was extremely kind to me and generous with his time from the very beginning. We kept in touch, and a few years after my graduation we taught a seminar together at Columbia. I was young, fairly new on the field, and Joseph, of course, many orders of magnitude my senior. And yet he treated me as an equal throughout. For instance, the students had to write three papers. I graded the first group of papers, he graded the second. Then I suggested that I grade the third, because, come on, equality is nice but let’s not overdo it. He was very surprised, but at the end said ‘well, if you insist’. I also remember that some of the course evaluations said things like ‘judging just by Raz’s demeanour in class, you wouldn’t know how great and influential he is.’

While the co-teaching was great, what I remember most from this term is our one-on-one meetings (usually, at some place in the Village where, he was delighted to find out, they served excellent pizza that only had the kinds of cheese he was allowed to eat). There I received excellent comments from him on papers in different topics (in epistemology, for instance), and he was the most open-minded about critical comments I gave him.

Joseph was such a good – and sometimes merciless – philosopher, that not everyone felt comfortable engaging him head on.

But my experience was totally different. When (a few years after the Columbia seminar) we taught together a PhD crash-seminar at the Hebrew U, most of the sessions consisted in me presenting and criticizing papers by him, then him responding, then discussion. And he was wonderful throughout. Including once, when I tentatively suggested that there was a fallacy in one of his arguments. From that point on until the end of the session, whenever he referred to that argument he referred to it as ‘the bad argument’.

And when – after he presented a paper at a workshop in his usual, less than ideal-speaker kind of way – I told him ‘It’s a good thing your claim to fame doesn’t depend on your presentation skills’, he took it in the best of spirits, and laughed and laughed.

More than once it happened to me that years after talking to Joseph about something, or reading him on a topic, I finally got it – I had the feeling that he was anticipating a move it took me so much time to recreate in my own mind, he was just several steps ahead of me. So while I was not, strictly speaking, a Raz-student, one of the compliments I love most is when some people think that I was.

Professor Stephen Perry, University of Pennsylvania Law School

My first academic appointment was with the Faculty of Law at McGill University in Montreal. In the fall of 1988, when Joseph was visiting at Yale Law School for a semester, I invited him to give a paper at McGill. For the day after Joseph’s talk, my then-partner and McGill colleague Alison Harvison Young and I planned an excursion to the Laurentian Mountains. Noam had accompanied Joseph to Montreal, and the idea was that the four of us would do a little hiking, witness the splendor of the leaves turning color and, for Joseph, take photographs. But it was not, in any conventional sense, a very successful outing. It poured rain almost the entire day, we all ended up thoroughly muddy and drenched, and the conditions for photography were terrible. Joseph knew that Alison and I were distressed by this turn of events, and I still have the letter he sent us afterwards. It read in part: “It’s funny how in retrospect, even only two days later, the rain on Saturday, instead of being something we managed to enjoy in spite of it, has turned into one of the things which made our expedition a success.” Although one of my earlier selves, the one who had encountered Joseph in his room at Balliol circa 1982, might have been surprised to hear me say this, Joseph was one of the kindest people I have ever known.

On February 27, 1993, when I was in Oxford for a reason that I cannot now recall, Joseph and I drove to Fyfield to have lunch at the White Hart. I know the precise date because it was the day after the first bombing of the World Trade Center in New York. We had a pleasant meal and an engaging conversation, as we always did on such occasions. Joseph talked a great deal about the event in New York, because he thought it portended more ominous things to come. He was, of course, quite right about that. After we’d finished lunch, Joseph said he thought he’d like to buy a television and asked if I wished to accompany him. Curious about this spur-of-the-moment shopping expedition, I said yes.

We drove to an appliance store in Oxford and, after a conversation with a salesperson that couldn’t have lasted more than twenty minutes, Joseph purchased a new and not inexpensive JVC television. I remained silent throughout this transaction, but he knew what I was thinking. He said something like, “you’re wondering how I could make a snap decision to buy such a costly thing without doing any research beforehand, aren’t you?” When I answered in the affirmative, Joseph said that he trusted the market to do his research for him and that the JVC would very likely be at least as good as any other television he might have bought. His words implicitly carried a mild reproach, since he knew that, before making decisions of all kinds, major and minor, I often engaged in just the kind of exhaustive research that he had forgone in buying the television. He was, I think, gently suggesting that such behavior can involve a significant opportunity cost; the aggregate time it consumed could have been more productively devoted to writing an additional article or two.

Over the years, Joseph and I generally tried to get together whenever I was in England or he was in New York. Sometimes I was invited to dinner at his spectacular apartment, designed by Noam, overlooking the Hudson on Riverside Drive. On those occasions when Penny could be in New York, she and Joseph would prepare a marvelous meal and the conversation would be particularly animated. When Joseph was alone, he would order take-out for us. In this, and in many other ways, he was a natural New Yorker. Sometimes we would go on cultural outings together. I have particularly vivid memories of going with him to a Seurat retrospective at the Metropolitan Museum in New York and attending a performance of The Lehman Trilogy at the National Theatre in London. On July 12th, 2018, I attended a performance of Don Giovanni at Covent Garden, which Joseph also saw on a live stream, at home in his London flat. The next day, we got together to talk about the merits of the production. We had no way of knowing that this was the last time we would ever speak. I’m glad that our final conversation was a lively discussion about opera, an art form that we both loved deeply.

Photographers: Gillman & Soame, www.gillmanandsoame.co.uk

Professor Joshua Getzler, University of Oxford

I went to China a decade ago for a conference on the rule of law, an experiment to see how Western liberals might explain this totemic ideal to those from a different legal and civilizational culture. I don’t remember much of law or rule that we debated that week, but I do recall the excitement of being in Beijing for the first time, and the even greater magic of generous time with Joe and Penny, who I knew from Balliol student days. Joe spoke with such softness, such quiet conviction, and seemed so august and measured, until the laughter broke out, and I saw that he was so often pulling my leg.

His capacity to surprise was unending. His arguments on Israel/Palestine flummoxed and made more thoughtful the most ardent partisans. He offered the thought experiment that marriage should simply be abolished as a legal category to prevent the harms it caused by exclusion. His staggering analytical work on rights, interests, authority, responsibility, freedoms, seemed informed by deep passions and hard-won experience, that he would always guard and keep private as he gave his public reasons.

Always more alert and alive with Joe.

Professor Aileen Kavanagh, Trinity College Dublin

I was supervised by Joseph Raz in the late 90's. I remember him, above all, as a kind, gentle, considerate, humble, thoughtful man with a deep sense of fairness and integrity, a large sense of humanity and compassion - and a mischievous sense of humour.

To be supervised by Joseph was a privilege and an honour. But it was also an academic boot camp like no other. In our first meeting to discuss a paper I had written, he spent almost two hours detailing the problems on the first page - of a 30-page paper. But he then took me out for lunch and we chatted about life in general. By giving me his focused attention and formidable criticism, I got the education of a lifetime from one of the most brilliant and influential philosophers of the 20th and 21st century. I have never taken that for granted and treasure it to this day.

When I was doing my doctorate, I was one of maybe 15 other students doing doctorates with Joseph across a staggeringly broad range of topics in legal, political and moral philosophy, but other topics too, including constitutional law, international relations and contract law theory. We used to meet up to share war-stories, but we also exchanged fond tales about his distinctive mannerisms, his sharp wit, his memorable turns of phrase, and of course, his scathing criticisms. He sometimes hosted parties for us in the front room of his house off the Abingdon Road. He laid out drinks and nibbles, and then enjoyed the party to the full, as did we. After tutorials, he would sometimes take us for lunch to see how we were doing. He cared. He was interested in our general well-being, not just our doctoral dissertations.

Looking back, I can see that he probably didn’t have to supervise as many students as he did. It was a huge amount of work. He could have spent his time swanning around the world giving papers, holding forth, and receiving accolades - living the life of the great philosopher on tour. But he did not think in those self-centred and self-aggrandising terms. He saw teaching and supervising as a core part of his role, which he took very seriously. Every term – and I mean, every term - he humbly and dutifully invested significant time, energy, insight, knowledge and whatever tact he could muster, into his students - into us. What a priceless gift - not only to those of us who were lucky enough to have been supervised by him – but to the University of Oxford and, more broadly, to the world of legal, political and moral philosophy. He educated the next generation. He shaped the contemporary landscape of analytical legal theory.

In The Morality of Freedom, Joseph says that a good life depends on having valuable, flourishing relationships, together with satisfaction in one’s work and successful pursuit of one’s goals. By those standards, it seems that Joseph Raz had a good life. In the various discussions with him over the years - especially in New York where I got to know him a bit better - it was always apparent how central Noam and Penny were to his happiness, as were his life-long friends around the world, to whom he remained loyal and committed.

It was an enormous privilege to have been supervised by Joseph Raz, but it was sheer pleasure and joy to have known him and spent time with him.

Professor Kimberley Brownlee, University of British Columbia

I was incredibly lucky to have Joseph supervise my DPhil thesis on civil disobedience alongside John Tasioulas (the lead). John and Joseph did me the kindness of marching in lockstep in their advice on what needed to be fixed in my thesis. Joseph was also remarkably supportive of my work on a chapter that criticized his views. I remember walking up to his rooms in Balliol to discuss that chapter, feeling breathlessly nervous. Once we sat down, Joseph tried to give me confidence by referring to his own work in the third person: ‘In this section’, he said, 'Raz argues X…’ I found that I did not agree with him that ‘Raz’ had argued X in that section, but I couldn’t say so directly. So, I used the passive voice: ‘Well, I believe that, in that section, it is argued not X…’ We went back and forth like this for a bit until Joseph chuckled and dropped the third-person, saying: 'My view is X. You may criticize that.’ I happily went away and did so. In addition to supporting my work, Joseph was a quiet but effective advocate as a referee. I am enjoying a wonderful career, and his endorsement undoubtedly played a role in launching it. That said, Joseph’s greatest influence on me - as on many contemporary moral and political philosophers - is intellectual. I return again and again to key ideas in his work, not just in his work on civil disobedience, but also on the interest theory of rights, practical reason and value, authority, autonomy, and liberal perfectionism. Each time, I have been philosophically enriched, and inspired to bend, twist, stretch, and invert his ideas. I am profoundly grateful for the chances I have had to work with, and learn from, Joseph.

Photograph by Ulrike Heuer

Professor Hillel Steiner FBA, University of Manchester

Having known Joseph for over fifty years, I certainly count myself among those fortunate persons who have been beneficiaries of his generosity, hospitality, insight, encouragement, and his wonderful sense of humour. His death came as a shock and will certainly remain a source of abiding sadness, lightened only by its prompting so many fond recollections of the enjoyable occasions I spent in his company. Of these, one that’s particularly salient in my memory is the day he introduced me, in his Balliol room, to his first and only recently acquired laptop computer. Being completely computer-illiterate at the time, I was overwhelmed by the almost child-like glee with which he proceeded, for well over two hours, to demonstrate its numerous magical capabilities.’

From the Convenors of the Oxford Jurisprudence Discussion Group: Cécile Degiovanni, Mauricio Garetto Boeri, Andreas Vassiliou

It was three years ago when Joseph Raz presented for the last time at the JDG with comments by David Owens. This week David will be joining us for another great session. But unfortunately Joseph Raz will not be with us. It's still hard for us to realise that we will not get the chance to have Raz in one of our seminars again.

One of us works on his concept of exclusionary reasons; one of us owes him their scholarship; all of us have taught him to undergraduates, marvelled at his rigour and, dare we say it, sometimes grumbled at some of his more intricate pages. This is but a little sample of the many ways in which DPhil students like us may have the great figure of Joseph Raz intertwined with their own intellectual path.

We are the last generation who will also have had the pleasure and honour to meet him in person. How precious this is cannot be reduced to the charm of the anecdotes we sometimes got out of it (like a certain conversation about dignity and streetlamps which one of us had with him, without the slightest idea, at the time, of who he was). Being able to have a chat and share some post-seminar cakes with such a great mind reminds us of why we enjoy academia: because it is not only an exchange of arguments, but an interaction between persons... real persons, with big hearts, big smiles, and sometimes big beards.

Joseph Raz was not only one of these persons; he was the occasion and the centre of thousands of such exchanges and interactions throughout the world, and the web of these discussions will only grow denser from now on. Inside and outside the walls of Raz’ very college, the JDG will be proud to keep providing a forum for these exchanges and interactions on our shared subject of jurisprudence to which his contribution cannot be overstated.

Joseph Raz, Central Park, New York. Photo by Alex Ward

Professor Brian Bix, University of Minnesota

Some Memories of Joseph:

(1) In preparation for one of my first discussions with Joseph about my writing (as a D. Phil. student), I had sent him a long analysis, where I started from notions generally accepted in the literature, but eventually took a novel position, and I was far from confident about my argument for that position. To my surprise, Joseph spent most of our time together challenging me on views I thought were accepted by all -- he kept asking ‘why think this?’ I quickly learned that convention and consensus were never acceptable justifications. As our time was running out, it occurred to me that we had never gotten to the part of the work I had initially been most worried about. I asked: ‘what about that last part of the argument

Photograph by Ulrike Heuer

Dori Kimel, University of Oxford

The Acknowledgements section of my first book began thus: ‘Through his work, as a D. Phil supervisor, as a colleague and as a friend, Joseph Raz has been an indefatigable source of inspiration and support. I cannot begin to put into words my affection for him and my gratitude.’

That was nearly 20 years ago. In the intervening years, the strength of these sentiments only grew. I still cannot put my affection and admiration for him into words.

Horacio Spector, Universidad Torcuato de Tella

I met Joseph Raz in 1979 when I attended his SADAF intensive graduate class on legal philosophy in Buenos Aires, Argentina. A few years later, on December 10th, 1984 Joseph Raz wrote me a brief letter in which he encouraged Guido Pincione and me to visit Oxford from Germany: ‘Once in Germany I hope you will be able to organise an extended stay in Oxford.’ We had arrived in Mannheim, Germany, in February 1986, as Humboldt research fellows, to work with Hans Albert, the champion of critical rationalism in Germany. Probably Raz had not realized that hosting two Argentine young scholars (Guido Pincione and myself) as Humboldt ‘Europe fellows’ would involve some consular difficulties. The UK still considered Argentina as an enemy country, after the Falklands War in 1982. So we needed special visas to enter the UK.

In retrospect, it sounds funny how Joseph reacted to our phone call from Mannheim. Guido was in charge of this difficult task. The German operator found Joseph's phone number in the old international directory very efficiently and put Guido through to Joseph, who remained a few minutes silent after hearing ‘Hello Joseph, this is Guido Pincione from Mannheim; I am with Horacio.’ Joseph chose his words on the phone very carefully, as if being recorded by the M16. But finally, he pronounced something like: ‘I will see what can be done.’

As we were trying to smooth the procedure to get the visas, we knew that the consular authorities would not grant us permission to enter the UK without a formal letter of invitation from Oxford. (Albert had written a very long letter addressed to the British consulate in Düsseldorf in support of our application.) Eventually, Joseph got us two letters dated 31st July 1986 from Professor Denis Noble, FRS, and Praefectus of the Balliol Graduate Center. The letter said: ‘This is to certify that Mr. Horacio Spector has been invited to Oxford as an Associate Member of the Balliol Graduate Centre here at Holywell Manor’. Very generously, Joseph found a way to allow us to have ‘our extended stay in Oxford’.

We arrived in Oxford in early October, before the beginning of Michaelmas term 1986. Joseph was very kind and even invited us to a social meeting at this house. (We were confused by the address and got to this house with a great delay, but he was nonetheless very nice when he welcomed us at the front door.)

Joseph was very generous with his time. Thus, he would read and discuss our papers in great detail. The sessions at Balliol were philosophical rollercoasters. I sent him my draft A Theory of Moral Ought Sentences, written with Aleksander Peczenik from Lund, Sweden. After one week or so, Joseph called me and pronounced these magic words: ‘Horacio, I enjoyed reading your paper; please come to my office tomorrow at such and such time’. As I remember, in our first meeting Joseph tried to show that my argument led to some kind of contradiction. I can't remember exactly his subtle point, but I do remember that it had to do with the Continental distinction between weak and strong permissions, which I accepted and he rejected. I would try to defend myself by challenging one of his assumptions, at which point he would show an impish smile. I realized that he was enjoying putting me up against the ropes.

Another feature of my first session with Joseph at his Balliol College office was less conventional. It was obvious to me that he did not like the idea that I would write the paper with Alek. He asked me, with a harsh tone: ‘What has Aleksander Peczenik to do with this?’ I explained to him the story of our intellectual partnership, which had begun in Buenos Aires in 1984. I liked Aleksander, but it is true that I had written most of the paper. I didn't say that to Joseph, but he suspected it.

Alek did not like Joseph either. When I told him that I would discuss the paper with Raz, he cautioned me: ‘Be careful, because Oxford guys have very liberal ideas about copyright.’ This also sounds funny now.

Photographers: Gillman & Soame, www.gillmanandsoame.co.uk

Professor Lawrence Alexander, University of San Diego

I have a few Joseph Raz stories. But the one I'm going to tell took place in 1977. In the summer of that year, the National Endowment for the Humanities funded a five-week law and philosophy ‘summer camp’ on the campus of Williams College. I can't remember the names of all of the thirty or so people who attended, but here or some, in no particular order: Myke Bayles, Bernard Williams, Charles Fried, Alan Wertheimer, Steve Darwall, Steve Munzer, Carl Cranor, Conrad Johnson, Gerald Postema, Wade Robison, Hans Oberdiek, Ronald Dworkin, and Raz. The days consisted of morning lectures by the more notable invitees--e.g., Dworkin, Raz, Williams, Fried--and afternoons devoted to recreation. For me that was pick-up basketball and golf. There were also occasional softball games, one memorably umpired by Dworkin, who alternated his umpiring between the model of rules and umpire's discretion.

Raz's lectures were analytically powerful. Dworkin's lectures, though characteristically unmatched in terms of their rhetorical power and style, some of us, Raz included, found particularly galling. For when Dworkin would say A, and then be challenged by someone--often Raz--pointing out that A would lead to an absurd result, Dworkin would respond by denying that he had said A and asserting that it would be ridiculous to assume that he had said A. And he would do this so forcefully and yet gracefully that the critic wouldn't know how to respond. I had had Dworkin as a teacher, but I had never witnessed this piece of Dworkin legerdemain before. You the reader have undoubtedly witnessed this Dworkin performance yourself--perhaps many times.

When it was time for Raz to depart from the summer camp, I drove him to the Albany airport, giving me an hour alone with him. I learned that he was not only disappointed but somewhat miffed that Oxford had chosen Dworkin, not him, for the chair in jurisprudence. And I could understand why Raz felt this way but also why Oxford had chosen Dworkin. In terms of substance, I thought Raz was Dworkin's superior. But in terms of style, no one, Raz included, could top Dworkin. And Oxford had gone for style over substance.

Professor Stephen Munzer, University of California at Los Angeles

Those of us present for the NEH summer camp at Williams College were blessed to learn from, and wrestle philosophically with, Dworkin, Raz, and Bernard Williams. The contributions of these three were remarkable, albeit in different ways. I couldn’t tease out the differences – even from my limited point of view – without a great deal more thought. Over the years I had more contact with Dworkin than Raz, though I don’t think that would affect my philosophical estimation of either.

I had never heard the Albany airport story until Larry’s email today. One can understand Raz’s disappointment that Dworkin was chosen over him for Hart’s chair at Oxford. But it is worth noting that Dworkin was about 37 when he became Professor of Jurisprudence at Oxford in 1969, whereas Raz would have been about 30 then.

At least one other participant at the Williams summer camp in 1977 was M.B.E. Smith, aka Barry Smith.

Professor Yossi Nehushtan, Keele University

I had the life-changing privilege of having Joseph as my BCL dissertation supervisor, then my MPhil supervisor, and finally my DPhil supervisor. I cannot imagine my academic career, abilities, thinking, and identity, without his caring and challenging mentorship. Joseph was a philosophy giant and legend not just because of his timeless contribution to legal, moral, and political philosophy, but also because of his rigorous supervision style and the time he dedicated to his students. And I was no exception. I owe him my academic brain. At least the good parts of it.

When we first met to discuss my written work, he gave me comments on a draft I sent him. I wanted to impress him with my commitment, so I told him that I will reply to his comments within 2 weeks. He looked at me and said: 'if you reply within 2 weeks, it will mean that you have not thought about my comments well enough'. And when I carefully read his comments, I understood why he said that. EVERY comment I ever got from him made my brain explode. And after every explosion, my brain improved... having Joseph as my supervisor was the most challenging, enjoyable, and beneficial experience of my academic life.

After I graduated, I visited him in London as often as I could. It was always over a superb lunch or dinner which was always his treat. I kept telling him that I am not a poor student anymore and that I can finally afford paying for my meals, but he never listened.

The last time we met was a few months ago, in London. His brain was as sharp as ever, but I had a disturbing feeling that that was our last meeting. His last words to me were 'be good, Yossi'... and like with almost everything else he ever told me, I spent hours (over)thinking what he meant by that. Shall I be good at what I do? shall I be a good person? shall I stop being a rebel and start obeying authorities every now and then?...

Everything in life disappears. Time, opportunities, hopes and dreams, people who we loved, memories, the persons we once were, the persons we are now. Everything eventually disappears. But some people leave a mark in other people's lives. They change them - and their lives' course. These changed people will then sometimes change the lives of others. The way I work with my students and care about them, is a direct result of my experience with Joseph. Very few people affected their students the way Joseph did. That impact, both academic and personal, will not easily disappear.

Thank you for everything, dear Joseph, and be good...

Professor José Juan Moreso, Universitat Pompeu Fabra

With deep sadness, I have noticed that this morning Joseph Raz passed away. I'm really so sorry. We'll miss him, his superb philosophical talent and his lessons. Now I remember him saying to Pablo and me at his Balliol office in 1995: 'Philosophy is not playing games, philosophy is solving problems!'

My condolences.

See also Professor Moreso’s obituary of Joseph Raz in El País: ‘Joseph Raz, la sensibilidad a las razones’

Joseph Raz, Central Park, New York. Photo by Alex Ward

Professor Jeremy Waldron, New York University

I have the good fortune to have had Joseph Raz in my life since around 1980. More than forty years. A mentor--and a highly critical one--for all that time. For all of us in fact. A colleague at Columbia for many years. A neighbor in New York. A giant whose thinking loomed so large for us all. But one who was also playfully present as a friend, with delight and good counsel. He made us all better. Someone whose presence at the NYU Colloquium over the past few years--with his soft voice and seismic insights--taught us the real meaning of authority.

See also Professor Waldron’s article on Joseph Raz in The New Statesman, ‘Philosophy’s gentle giant: Why Joseph Raz was one of the most important theorists of our age.’

Anonymous

Once upon a time in a country pub outside Oxford I suggested to Joseph the way I thought one could deal with a philosophical problem that interested me. The questions he raised took me a book to answer.

Jeffrey Hackney, Emeritus Fellow, St Edmund Hall and Wadham College, Oxford

Penny,

My face lit up whenever I met Jo. It lit up even more when we talked and yet again if you happened to join our conversation.

Very much missed already.

Warmest best wishes

Jeffrey

Sebastian Lewis, University of Oxford

I wrote an email once to Joseph Raz because I was working on a paper on legal reasoning in which I discussed some of Raz's views on common law theory. To my surprise, Joseph's response came with an invitation to discuss my paper in his flat in London. We spent more than three hours talking about life, music, law, philosophy, and photography.

I’ll always remember that moment, which has been one of my greatest academic joys and honours, as a unique token of kindness from a titan in philosophy to a struggling student.

Professor Niki Lacey, London School of Economics

I first met Joseph in 1980, when he kindly agreed to supervise my BCL dissertation. Responding to his meticulous scrutiny of my work, and the intense discussion of each supervision, were undoubtedly the most intellectually demanding parts of my two year course. While I was at New College, we saw one another regularly: I remember the keen concentration needed to enjoy the full benefits of conversation with Joseph as one struggled to hear his soft voice amid the hubbub of an Oxford common room. We taught a Philosophical Foundations seminar together; and later on, Joseph was a keen interlocutor, interviewee and (mainly!) sympathetic critic of my biographical work on Hart. By this time, it was clear that my intellectual trajectory had gone in a different direction to the one which really commanded his interest. But his work, of course, remained hugely important to me, and I shall always feel lucky to have been able to learn from and work alongside such a giant of jurisprudence. Perhaps the deepest tribute I can make to his intellectual friendship is that his ideas on momentary and non-momentary legal systems, which were the object of my BCL thesis, have echoed through virtually all of my work over the last 40 years.

Penelope Bulloch and Joseph Raz, New York. Photo by Alex Ward

Joseph Raz and Penelope Bulloch, New York; photograph by Alex Ward

Professor Ori Herstein, the Hebrew University of Jerusalem & King's College London

Joseph Raz vignettes:

Joseph was my dissertation advisor, mentor, and friend. Technically, he was also my colleague at King’s College London, although in this case ‘colleague’ feels to me presumptuous. Altogether, I knew him for nineteen years. Following are a few memories of our times together, which I will always cherish.

Coming to dinner at our London flat with Penny and our friend Sandy, Joseph passed on the borscht – ‘I did not like it when my mother made it for me, and I still don’t like it’. This statement made my wife (born in Moscow) wonder exactly how deep Joseph’s Russian roots ran. A couple of years later in Israel, she (cunningly) sharply shifted to speaking to our boy in Russian in Joseph’s presence. This elicited amusement from Joseph, who seemed to more or less make out what she was saying. She later threw an antiquated Russian curse word into a story she was telling us; resulting in Joseph perking up (‘Haa!’), as the dormant memory of a word he had seemingly not heard in decades suddenly seemed to reappear before his mind’s eye. ‘That’s it,’ she later exclaimed to me, ‘Joseph blew his cover!’

Borscht aside, Joseph enjoyed fine food and drink. So much so, that it seemed as if all his neighborhood restaurants knew him. When at his local Indian restaurant, Joseph would pour his curry on flat naan bread, spread the sauce around, and proceed to eat them together with a knife and fork. No rice. We shared many meals. In fact, my one and only time at a Michelin Star restaurant was with Joseph. He suggested the restaurant. It was terrific. And he paid.

In my first year as Joseph’s PhD student, I bumped into him and Penny by the Columbia Law School’s elevators. He smiled and nodded, and then we stood there waiting in silence. When we walked into the elevator, I politely removed my iPod earphones (it was 2005). ’What are you listening to?’, Penny asked. ’Jacques Brel’, I said, explaining that although I do not speak French, I like his music nonetheless. Joseph replied ‘I feel exactly the same way,’ looking at me inquisitively, as if considering whether there was more to this Israeli guy than meets the eye.

Joseph and I sitting with our feet slightly elevated at the far corner of the Columbia Law School faculty lounge. Spending half an hour discussing the previous day’s seminar with Ronald Dworkin. And then spending the second half hour gossiping about the previous day’s seminar with Ronald Dworkin.

Favorite Joseph saying: ‘there is a wobble in the argument’.

‘I thought you did well in the viva, and the dissertation is good, so that you fully deserve your elevation from the status of a student to the higher one of a Dr.!

Joseph’

[I have this email framed]

Driving Joseph from Tel Aviv to Jerusalem, I spoke with him of a PhD student of mine. The student, I told Joseph, was by far more capable than I was at that stage of my own career. Joseph said nothing. Yet he seemed elated with this statement. I think it was his proudest moment of me as his student.

Joseph coming to my aid when defending a paper at the daunting Analytic Legal Philosophy Conference.

Having written some critical remarks about another scholar, I was worried that they must now hate me, and will surely destroy my career. Walking together back from lunch by his London flat, I confided in Joseph. With a wry look on his face, he informed me that ‘there is no reason here for paranoia’.

I once sought Joseph’s advice about whether or not to stay in London fulltime or to move to Jerusalem. Numerous conflicting emotions, considerations, and calculations were pulling and pushing me in both directions. ‘I do not know how to approach this matter. It’s too complicated’, I told him. Joseph looked at me and said, ‘just be rational’.

When our son was born, Joseph asked my wife what our baby boy had taught her about the world. Years later, every now and again she still ponders the question.

Trying to keep up with Joseph walking the streets of Central London. Trying to keep up with Joseph walking the streets of the Upper West Side. Trying to keep up with Joseph exploring the gorgeous campus of Cornell University.

Jump to the top

Dr Penelope Bulloch, Emeritus Fellow, Balliol College

This was a poem that expressed what Joseph felt at the moment, with the invasion of the Ukraine, and other conflicts, and it meant a lot to both of us.

Dover Beach

The sea is calm tonight.

The tide is full, the moon lies fair

Upon the straits; on the French coast the light

Gleams and is gone; the cliffs of England stand,